Sailor's new mission serves veterans struggling with substance abuse and mental health

The incident in June 2016 should have never happened.

The ember shouldn’t have ignited into a blaze of depression and anxiety, suicide attempts and alcohol abuse. Jail. When the 35-year-old applied for financial assistance from the Gary Sinise Foundation, he was understandably reluctant: Why would they help me?

The Florida sun beat down on the C-130 parked outside a hangar at Naval Air Station Jacksonville. The summer day was hot, the air blanketed with humidity. For hours Paul Short’s five-foot-five body was wedged into the cramped confines of the plane’s tail. A structural mechanic, it was his job to inspect the herculean aircraft. Wearing the standard issued coveralls, he sweated profusely.

“There’s supposed to be somebody who’s watching you from down below, and their main job is to help kinda pull you out and stuff,” Short said. Left alone, no one heard him pounding from inside the tail. No one heard the desperation in his voice as he screamed for help. “I remember feeling like I was going to die.”

He passed out from dehydration, waking up hours later in the hospital. When Short returned to work, he felt the weight of the incident hanging on him like sweat-drenched coveralls.

Little more than a month after the incident, Short had a panic attack. He was at a bar with friends. “All of a sudden, I could hear everybody talking to me.” Their conversations, he said, were “amplified.” He described feeling like he was wearing a yellow sign that said, ‘Hey, this person isn’t OK.’

He was far from OK.

“I knew before I joined the military that drinking was a thing that guys in the military do. I mean, you’re always hanging out, you’ve always got a Bud Light in your hands,” he said. “I knew drinking was there, but it was never really an issue before in my life.”

Weeks after the panic attack, Short remembers walking into the base commissary and buying a bottle of Fireball whiskey. It was a Saturday afternoon. He returned home, sat down on the couch to watch the Univ. of Virginia football game, and in a blur, drank the entirety of the bottle, mixing cherry soda to mask the whiskey’s sweet cinnamon flavor.

“That was the first time where drinking ever accomplished something that I needed it to do,” Short said about passing out, “and what I wanted it to do was take my mind off the situation.”

As his anxiety and depression worsened, so too, did binge drinking. Counseling sessions became pointless, he said, much like taking antidepressants.

His father, Steven, wasn’t faring much better.

Nearly 470 miles separate Winston Salem, N.C. from Jacksonville, Fla. Between long weekends and taking an extra day of liberty, Short visited his father as often as he could. Steven’s health had taken another turn since having a stroke in 2015. But driving back and forth — a seven-hour trip one way — was adding up. “I was getting spread pretty thin on top of also trying to deal with my own issues,” Short said.

“Something was going to break eventually.”

The Navy reassigned Short for humanitarian reasons to a reserve station in Greensboro, less than 40 miles from his family’s home in Clemmons. Unlike his job at NAS Jacksonville, he had a lot more downtime. More downtime meant more time spent watching his father deteriorate before his eyes. More time to escape the quickest way he knew how.

“Me drinking, I knew it wasn’t going to fix anything. But whenever you wake up and the first thing you have to do is take care of a loved one who’s dying and at the same time, you can’t do anything, drinking starts becoming a pretty good outlet because it does its job — it makes you blackout,” he said.

“And that’s what you want.”

Since moving back home, his anxiety and depression only worsened. He wasn’t sleeping well. Only a year before did he attempt to drive off a bridge in Lexington, about 20 minutes from Clemmons. The police found Short intoxicated and asleep at the wheel; his car pulled to the side of the road not far from the bridge.

“I was wanting to die, and whenever you want to die, repercussions and consequences of actions have very little meaning,” Short explained. “If you think that within the near future that you’re going to end your life, what’s getting drunk and getting a DUI matter?”

In early 2018, he was at home when negative thoughts simmered out of control. “I was an embarrassment to the Navy, I couldn’t help my family out, I didn’t have my own wife and kids, and now I’m close to 30 years old, and I start feeling that pressure a little bit,” Short remembers thinking. Progress towards his master’s degree had all but stopped.

His mother found him sitting on his bed ready to strangle himself — one end of a leather belt tied to the bed’s backboard, the metal clasp cinched to his neck.

The suicide attempts were but one setback that year. In five months, he received three citations for driving while intoxicated. The state suspended his driver’s license for two years. And there was the day in May when his face splashed across the local news station after being arrested and charged with assault (the charge was later dropped).

In Aug. his mother checked him into Rebound Behavioral Health, an adult inpatient treatment and substance abuse rehabilitation center in South Carolina. For 30 days, clinicians and mental health professionals “didn’t just treat the alcoholism,” Short said. Rather, they treated both the service-related post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse.

By year-end, Short was discharged “under other than honorable conditions.” With Steven’s cancer in remission, he felt he was in a better place. He still battled depression and infrequent panic attacks, but was armed with a new counselor, new medication. He quit drinking and found temporary employment. The experience at Rebound was true to its name.

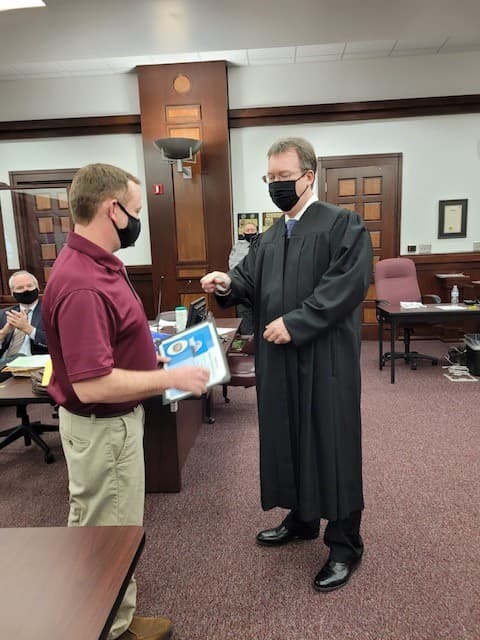

Little by little hope started unveiling itself at the latter end of 2019. While serving 45 days in county jail for the DWIs, Short’s criminal cases were moved to the state’s Veterans Treatment Court. According to the North Carolina Judicial Branch, a VTC is “similar to drug treatment and mental health courts in that they involve cooperation and collaboration with court officials, community partners, and law enforcement.”

For Short, that meant enrolling in substance abuse treatment, temporarily wearing an ankle monitor, random testing for drugs and alcohol, and weekly court appearances for the first six weeks of the program.

“One of the things you find when you deal with people with substance use disorder is that the use is the secondary disorder,” explained Genevieve Winderweedle, Short’s court-appointed caseworker. Winderweedle served in the Army National Guard and joined Harnett County’s Veterans Treatment Court in 2015.

To be sure, while the culture of acceptable drinking in the military is a huge problem, she said the real issue for veterans coming into the court, “is always mental health first.”

Short was a case in point. Clinicians found that the alcohol abuse and suicide attempts stemmed largely from childhood trauma and service-related PTSD.

In March 2021, Short’s father died of colon cancer. Steven’s death, and a hostile living situation at home, forced Short out of the house. “I didn’t have a cent to my name,” he explained about being homeless for weeks. “The money I was making it was going towards Ubers and Lyfts to get to and from work...I really didn’t have much, and whenever dad had got real sick, I ended up not working so much.”

The court later arranged for him a hotel room, but between rampant drug use he saw and the night he stepped on a cockroach on the floor of his room, his was a temporary stay. Through the court’s nonprofit, they found him an apartment. But with his meager earnings from detailing cars — $35 per vehicle — there was one hiccup: he couldn’t afford the monthly payments.

At Winderweedle’s urging, he applied for financial support from the Gary Sinise Foundation. He was ambivalent at first. Yet in nearly two years, he was back on track in his graduate studies. He was sleeping better and managing his anxiety and depression. Counseling sessions proved worthwhile. Sober, he was gainfully employed albeit eager to move on.

From Winderweedle’s perspective, Short is a shining example of the value of Veterans Treatment Court. He deserved help. And he had earned it.

While riding his bike home from work one June evening, Short heard his phone ring over the roar of rush hour traffic. It was an 818 area code — the Gary Sinise Foundation was calling. Standing off to the side of the road while cars zipped by, he was told that three months of his rent would be paid. The news shocked him.

“It was the first time besides Veterans Treatment Court that somebody has called me a veteran and has said, ‘Here, we’re going to help you.’”

Hard as he tried not to, he cried.

Short finishes Veterans Treatment Court next month. He’s on track to earn a master’s degree this fall in counseling and human development. He said he wants to work with veterans as a substance abuse counselor. With a clean slate, the veil of hope is no longer a flicker.

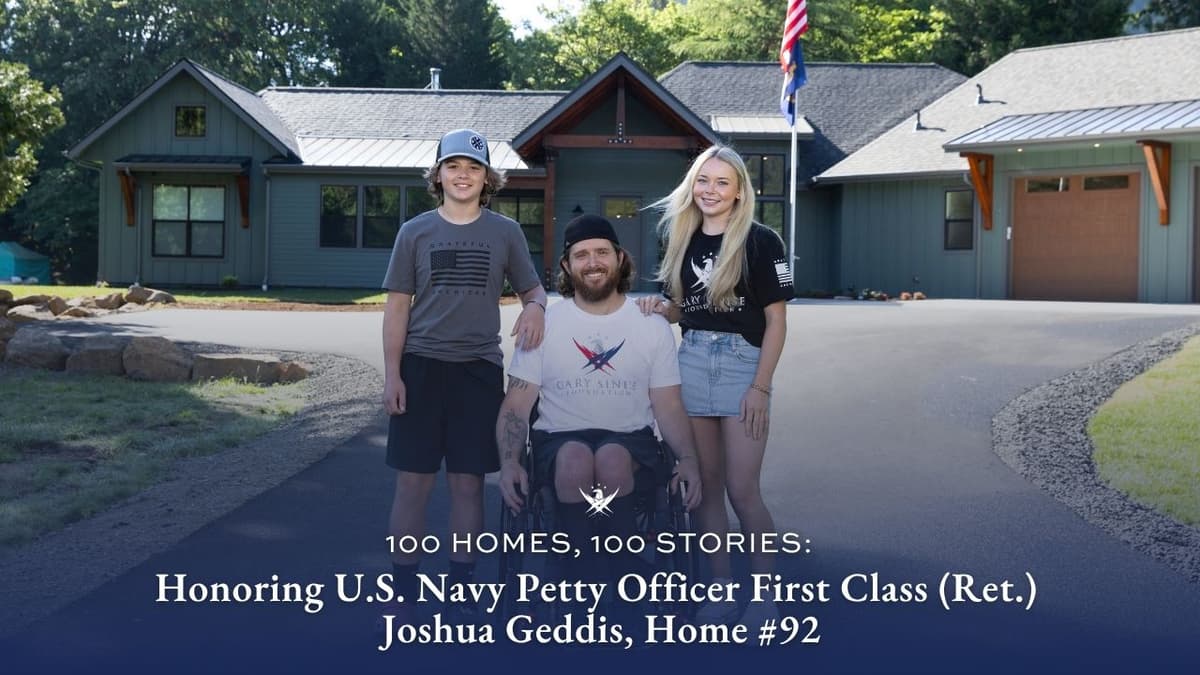

“It feels like the end of the tunnel is real close.”