Detroit WWII veteran reminisces about life, service, and music's golden age

When Bob Harris reminisces about his life, the 91-year-old Detroit resident describes it as “very, very interesting.”

He’s not kidding.

In the 1930s, he and his mother, Jeanie, moved from New York to Chicago, when organized criminal syndicates and gangsters were household names. Harris remembers characters like Pretty Boy Floyd and George “Machine Gun” Kelly, whose exploits made newspaper headlines. He was never too far from the action.

One day after school, he was walking back home on Chicago’s South Side when a sudden cacophony of noise startled him. He ran inside a nearby convenience store and asked the clerk about the commotion. “Oh, that’s just a bunch of police chasing a gangster,” the man told him. “They’re just shooting at the gangsters.”

There was the day he took a shortcut home through open fields that, unbeknownst to him, was controlled by a neighborhood gang. A confrontation ensued. The gang told Harris he was trespassing on their turf. Scared, he hustled away but not before one of the gangsters pulled out a pistol and shot him in the back.

Jeanie moved the two of them to Detroit to be near relatives scattered about Michigan. Months later, Imperial Japan shocked the world with a surprise attack at Pearl Harbor. As he and his mother tuned in to the radio to hear President Roosevelt’s address to a joint session of Congress the day after the attack, Harris knew then that he wanted to join the military.

A seemingly intractable problem given his age, yet the 14-year-old was unfazed.

Using the birth certificate of a neighbor’s deceased son born two years before Harris in hand, he quit school and took a job that ended up going nowhere. By 1944, like many of his peers inching to get in the fight, he lied about his age and joined the U.S. Merchant Marine. After a year, he enlisted in the Naval Reserve in Detroit. Nearly twelve months later, Harris joined the Army and shipped out to U.S.-occupied Japan, more than a year after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Harris, now 16, and the 46th Engineer Construction Battalion arrived at Atsugi Airdrome, west of Yokohama. The base was used by the best pilots in Imperial Japan’s navy to defend the mainland during the war. Relics of Japanese Zeroes and other aircraft still littered the airfield, a reminder of how not long ago, those same planes had mercilessly attacked American and allied forces.

Despite Japan’s formal surrender, Harris said his battalion encountered sporadic resistance from the Japanese. During a “rescue mission” of an Army general stranded in the hills above Yokohama, a blown bridge impinging the general’s travels, Harris and the 46th Engineer Construction Battalion were dispatched in the yawning hours to construct a Bailey Bridge in its place. As Harris recounts, “Well, while we were building it, we got fired upon.” Troops from his unit equipped with flamethrowers put a stop to the gunfire.

The audacious attack wasn’t the only surprise he encountered in Yokohama. While Harris’ memory is fuzzy about where he was at the time, he said he and Lou Nova, the 1935 U.S. and world amateur heavyweight champion, had an impromptu sparring session. (Nova was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1991.) Two weeks after he laced up his gloves and sparred with Nova, Harris recalls being on a boat and seeing him, “with two women and raising hell and waving at us.”

In Tokyo, Harris crossed paths with General Douglas MacArthur, who was acting military governor of Japan. Dressed impeccably in his Army’s best, MacArthur’s vehicle passed within 20 feet of Harris, who stood at attention in the street, saluting the vaunted hero of the Pacific. “I’ve never seen somebody with so much gold on their uniform – his hat was all gold; his shoulders were all gold – he was dressed in a lot of gold.”

After the service, Harris worked for Hudson Motor Car Co. in Detroit. In 1949 he married Hope Seftis. And by the early ‘60s, the family had grown to six kids as Harris made inroads in Motor City’s burgeoning entertainment industry.

In a career spanning five decades, Harris worked with some of music’s greatest icons. As a concert promoter, manager, and publisher, he said, “I’ve met probably 500 entertainers.” From Motown to jazz to rock ‘n’ roll, he rubbed elbows with a who’s who of talent: Frank Sinatra, Barbara Streisand, the Supremes, Bobby Vinton, Geno Washington, Smokey Robinson, and Stevie Wonder. There was also the night he met a young Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5.

But among his fondest memories is taking a photo with the Rolling Stones during their second American tour in 1965 at Cobo Hall (now TCF Center) in Detroit when he was the publisher of “Teen News.” Years later, in 1999, when the Stones returned to Detroit, Harris had Mick Jagger and the band autograph the photo when, as Harris proudly recounts, Jagger called him the “oldest Rolling Stones fan in America.”

For a brief period, Harris managed Three Ounces of Love. The trio was destined for greatness, he knew. But when the group went behind his back and joined the Commodores management team, a contractual dispute and lawsuit ensued. Said Harris, “I couldn’t believe they did that to me that I got out of the music business altogether because of that.”

In 2008, Harris co-wrote “Motor City Rock and Roll: The 1960s and 1970s." The book draws from his decades-long career in the music business and the hundreds of photographs he owns that chronicle the rise and popularity of Motown and Rock ‘n’ Roll in Detroit.

For all the attention and frenzy he witnessed musicians receive over the years, he never imagined that in July 2019, he too, would be at the center of attention, a focus of cheers and applause, photographs, and praise, during a three-day visit to the National WWII Museum in New Orleans.

“That’s one of the best trips I ever had in my whole entire life,” Harris said about Soaring Valor which is sponsored by the Gary Sinise Foundation. “I loved it.”

Like a reception for the Rolling Stones, throngs of people greeted Harris and a group of World War Two veterans and their caretakers at Detroit Metropolitan Airport and upon arrival at Louis Armstrong Airport. It was a ticker-tape-like celebration.

The spectacle took to the road: buses filed out of the airport, one behind the other, en route to the hotel, escorted by New Orleans police. Intersections and thru streets were blocked off. Traffic stopped. Police sirens blared, lights flashing. Said Harris, “They treated us like the president of the United States.”

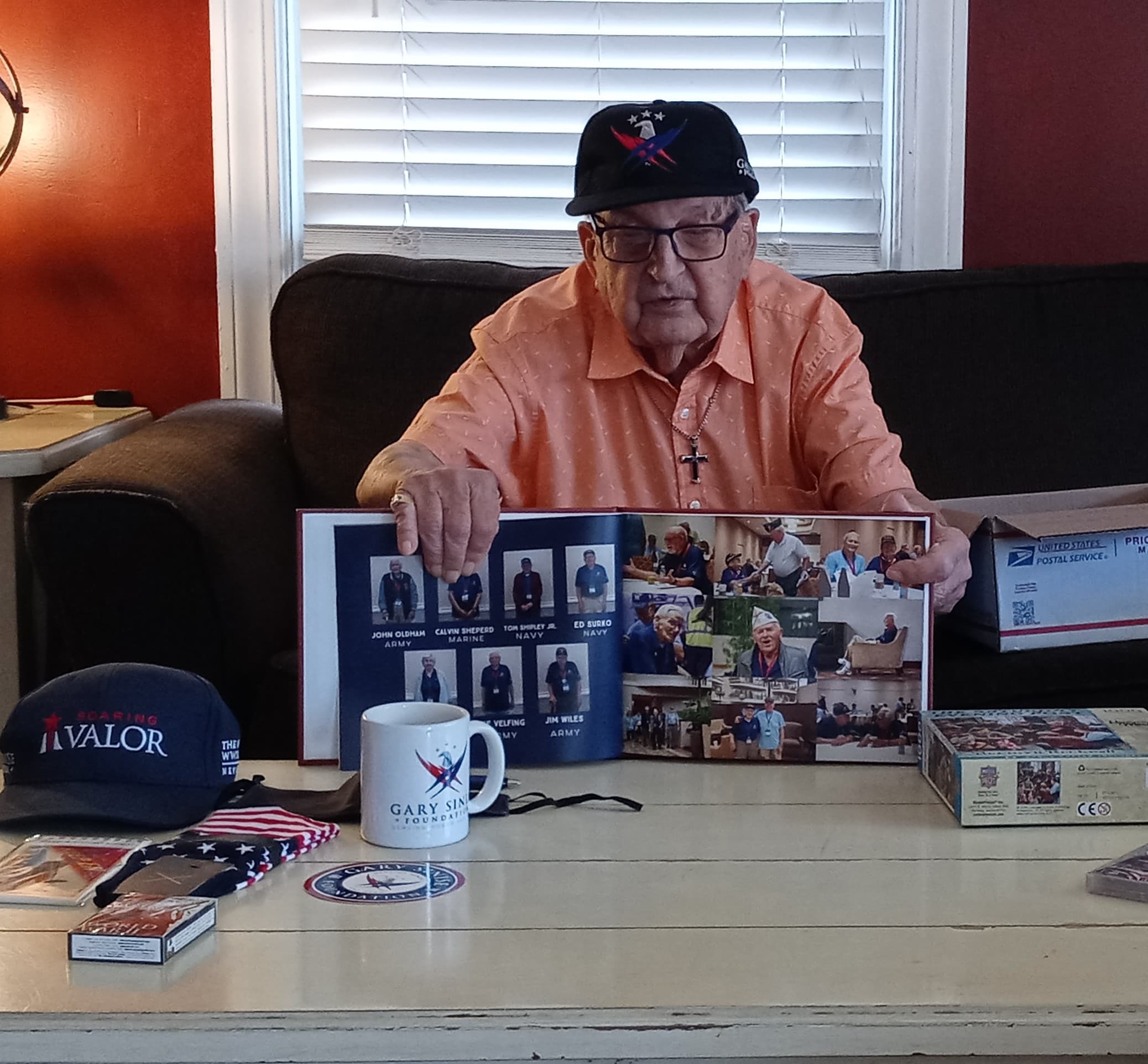

Last month, Harris received a care package from the Gary Sinise Foundation. Inside were a Bob Hope DVD, Gary Sinise’s autobiography, “Grateful American,” a foundation-emblazoned hat, and other items. But among the package’s contents, he cherishes a red album containing photographs of his trip to the National WWII Museum. “I’m in that book about sixteen times,” Harris said.

A special memento, not least because he counts 19 grandchildren, 30 great-grandchildren, and five great-great-grandchildren.

Towards the end of our hour-and-a-half interview, Harris said at one point about his life, “Do you want to know the bottom line to all of this?” “Yes,” I earnestly responded. He rattles off a non-exhaustive list of professional and personal achievements before saying with a subtle air of pride, “I don’t have nothing but a sixth-grade education.”

He’s not kidding.