ER nurses in San Diego and New York City. A Los Angeles restaurateur. A USO director. How the Foundation touched their lives in 2020 during COVID-19

60,795.

That’s the total number of meals the Gary Sinise Foundation Emergency COVID-19 Combat Service campaign delivered in four months to 313 locations in the United States and several overseas military installations.

Working remotely from their bedrooms, kitchen tables, and living rooms, the foundation’s staff put out phone calls and emails to hospitals, VA medical centers, and military bases en masse with a message: We’re here to help. What do you need?

Responses flooded in. At 273 hospitals and 145 VA medical centers across the country (an estimated 40 states in all), pre-packaged meals nourished doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals working on the front lines of the global health pandemic. Service members and their families stationed in Germany and Korea, too, received free meals and snacks.

Weeks before the campaign started on April 1, the foundation was already fielding COVID-19-related requests. Grant applications for purchasing personal protective equipment (PPE) came in one after another from first responder departments. Veterans, families and spouses of deceased service members, and others who found themselves furloughed from their jobs, laid off, or unable to enter the job market entirely were needing financial assistance, and fast.

More than 250,000 people have died in the United States from COVID-19 while 11 million cases and counting have been confirmed. Infections continue to rise nationwide as progress on a vaccine shows increasing promise with successful clinical trials from Pfizer and Moderna. As has been the case from the beginning, the critical demand on health care professionals and first responders alike remain unprecedented.

Eleven months into the global health pandemic, the cycle of COVID-19-related inquiries and grant applications continues. For the thousands who donated to the Gary Sinise Foundation, this is the fruit of the COVID-19 Emergency Combat campaign. And these are the stories of five recipients.

The USO Fort Campbell/Nashville executive director

First came the tornados late in the night on March 2 and early the next morning. Its path of devastation ripped through central Tennessee and the Nashville area. Days later came confirmation of coronavirus in the Volunteer State. A statewide “safer at home order” followed weeks later that saw businesses shutter and unemployment drastically escalate.

Unlike active duty service, the National Guard is primarily a part-time occupation. Having a second job to make ends meet is common. As businesses were closing, guardsmen weren’t immune to the economic ripple effects. “The families were really starting to feel an impact very quickly,'' said Kari Moore, who leads USO Fort Campbell and its two Nashville locations. The state’s guard assisted in cleanup and recovery efforts after the tornado passed through, and they continue to staff COVID-19 testing centers.

With financing from the Gary Sinise Foundation, in April, Moore and her team, including Kim McHugh from the Tennessee National Guard, turned to a local Kroger store and placed an order for 1,000 Hormel shelf-stable meals for guardsmen and their families.

“A lot of our soldiers have been to areas in Iraq and Afghanistan that have seen horrific situations,” said McHugh. “They’re very thankful for what they do receive simply because they know what it’s like to see nothing.”

At Fort Campbell in Kentucky, the USO center typically hosts 300 troops and families on base once a month for a meal paid for by the foundation. In Nashville, the USO supports the 118th Airlift Wing of the Tennessee Air National Guard, and further east, the 134th Air Refueling Wing in Knoxville. Their partnership with the foundation stretches back to 2014 (USO Nashville) and 2015 (USO Fort Campbell), respectively.

Moore attributes her ability to expand the USO’s presence in Tennessee to the trust developed over the years between the foundation and USO. “If we’ve recognized the need, the Gary Sinise Foundation will support.”

And support the foundation did. In August, with statewide restrictions on mass gatherings prohibiting shared meals together, the USO distributed 250 meal vouchers to airmen and families from the 134th Air Refueling Wing for use at Knoxville-based Full Service BBQ. Service members’ appetites weren’t the only beneficiaries.

Said Moore, “The infusion of the funds from the Gary Sinise Foundation was helpful at a really critical time for a local restaurant.”

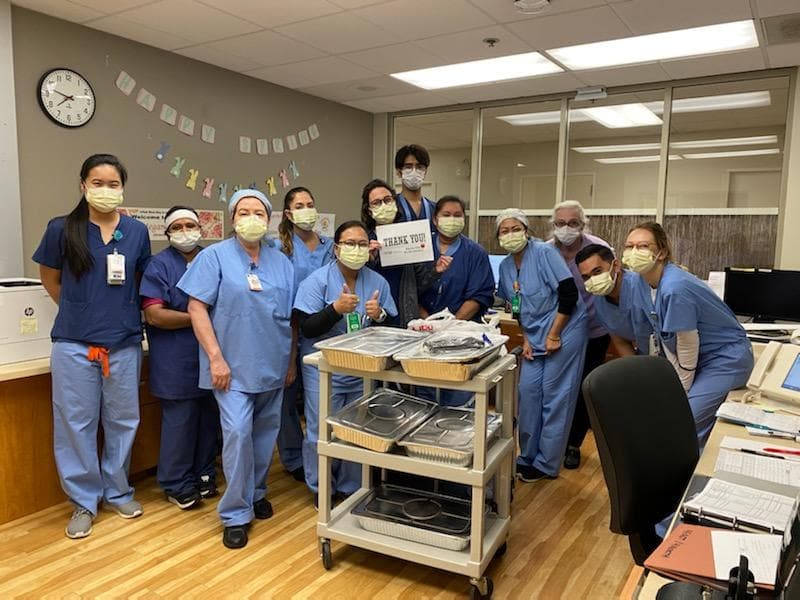

A San Diego COVID-19-unit nurse manager and an ICU materials specialist

“The fastest way to anybody in healthcare’s heart is through food. If you throw food into a hospital, it’s like wildfire,” said Sarah Saunders-Harbaugh, a nurse manager of a COVID-19 unit at Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center in San Diego.

Sharp Chula Vista in the South Bay has been one of the county’s hardest-hit hospitals since coronavirus cases began popping up in San Diego in March. South Bay neighborhoods, including five of Chula Vista’s six ZIP codes, were among the most impacted in the area whose residents tested positive for COVID-19.

Harbaugh said the hospital's staff have not been immune to COVID-19; two have died, and others have been infected. “I can’t imagine anything even futuristic being like this,” said Harbaugh, who joined the hospital in 2014. The emotional and psychological fatigue led some of her colleagues to leave the profession outright. Others took a temporary leave of absence to shore up their mental health.

Caring for COVID-19 patients month after month has worn down many on her floor. Harbaugh herself, rides a Peloton bike to keep sharp and relieve stress. She says a positive attitude is essential.

In May, pre-packaged meals from local eateries arrived at Sharp Chula Vista. For Harbaugh and other medical staff already into their 12-hour shift, going outside to pick up food was a break from reality and an opportunity to socialize (physically distanced), “I don’t want to say there’s a highlight in the disease process and the pandemic, but it was wonderful.”

For Tiffanie Burns, a materials specialist in the intensive care unit, the positive change in her colleague's demeanor was palpable, “It’s actually making us feel better about what we’re doing. It might be something as simple as a meal, but it’s actually doing something,” explained Burns, who has worked at the hospital since 2005. She said meals donated by the Gary Sinise Foundation, “Put a smile on a lot of people’s faces.”

The Los Angeles restaurateur

“Compared to pre-pandemic, our sales have dropped 94 percent. Where we were doing three to four thousand dollars in sales on a Friday night, now we’re doing maybe $300 on a Friday.”

Scott Teruya opened Marché Wine Bar in Burbank, California, six years ago. Business was good. Within a few miles of the full-service restaurant lay two entertainment behemoths: the Walt Disney Company and Warner Brothers Studios. The neighborhood also included a sizable presence of companies supporting the studios and entertainment industry in one way or another.

Teruya said he could count on a steady stream of regulars from the “biz” dining out at his restaurant, ordering bottles of wine from a curated list of Old World and New World wines, or just stopping in for a glass of vino or a cocktail and an appetizer. The coronavirus brought that consistency in business and comfort to a grinding halt. His nightmare was just beginning.

Bottlenecks in the supply chain and spikes in prices for beef and dairy products compounded a growing list of his problems at the outset of the pandemic. With variations of stay-at-home orders issued by governors in states across the country, even wine became an in-demand commodity. Letting go of his employees was a heartbreaking decision. He didn’t have a choice.

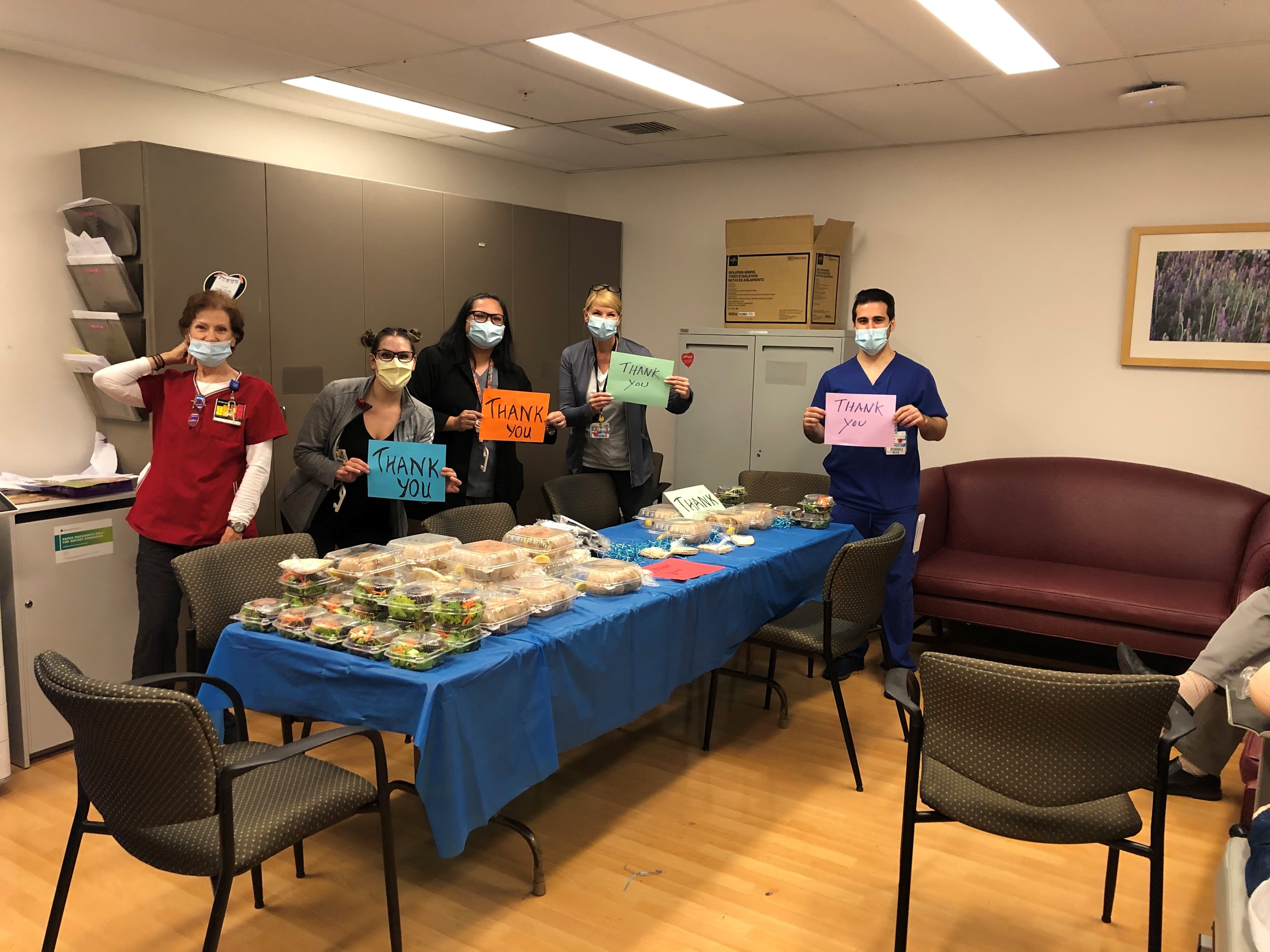

In early April, through an impromptu reference to the Gary Sinise Foundation, he was given a lifeline. From late April through mid-July, Teruya worked alongside his son, Robert, an eighth grader, preparing upwards of 75 meals (split between lunches and dinners) for nurses and staff at Providence Saint Joseph Medical Center in Burbank.

“Everything from barbecued pulled pork to braised boneless beef ribs sandwiches,” Teruya said about the revolving menu that also included homemade mac and cheese and grilled chicken. Dessert featured the restaurant's signature New York-style cheesecake.

Unsurprisingly, word traveled fast inside the hospital about the Thursday afternoon meals delivered to nurses and staff working that day’s shift. Teruya said it got to the point where he was told by one of the managers that hospital staff were rescheduling their shifts just to be on hand to have one of his homemade meals.

For a chef, Teruya said, that is the highest compliment you can get.

The New York City emergency department nurse

“I always knew I was going to do something in healthcare. I always knew it.” Lyzette Borrero grew up in Manhattan, and for as long as she can remember, she has wanted to help others just like her mother, a career healthcare professional in New York City.

Before joining the Mount Sinai Health System as a registered nurse, Borrero spent over a decade as a New York City paramedic. On the morning of September 11, 2001, she was with her daughter, Kayla, at a doctor’s appointment. The two watched as one of the towers came crumbling down onto lower Manhattan. It was the first time, she explained, that a sense of fear and insecurity took root in her.

It was an unfathomable attack, an unfathomable disaster. Then came the novel coronavirus.

“I never imagined in my worst nightmare that so many people would be ill at the same time. It wasn’t possible to take care of everyone all at once — everyone needed you equally.”

New York City became the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in March. Infected patients inundated hospitals, stretching health care workers and resources thin. Deaths in the city attributed to the microscopic virus at one point in early April reached 810 people. That same period saw over 5,000 reported cases of COVID-19.

At Mount Sinai West on Manhattan’s Lower West Side, the number of people streaming into the ER with COVID-19 symptoms, or worse, Borrero said, was like an “avalanche.”

“We would find that so many of them had such low oxygen saturations. A lot of them were either intubated or going on nasal [delivering high concentrations of oxygen], or masks.” Patients required constant monitoring of their oxygen levels. There was no letdown.

Borrero has treated countless infected patients since coronavirus made landfall in New York City in late February. In the “avalanche” of people coming and going from the ER, the 20-year-old woman who resembled her youngest daughter stands out among the others. Borrero said each time she went into her room, the woman repeatedly asked, “Am I going to be ok? Am I going to be ok?”

“I remember her face, and I remember wiping her tears, and I don’t know whatever happened to her,” Borrero said. “She was so young and alone and scared. And as a mom, my heart just went out to her.”

Throughout April and May, donated meals paid for by the Gary Sinise Foundation were delivered each week to the hospital’s emergency department shifts. “It was a nice break to sit down and have something delicious and warm waiting for you,” Borrero said. The surprise letters and cards and drawings that were occasionally included inside meal boxes, she said, was a welcome gesture. “You feel loved. You feel appreciated.”

Like in other parts of the country, New York City is seeing increasing numbers of COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations. Borrero said that the scale is not as bad as it was in the spring, but the current uptick is a serious concern.

With so much praise and attention lapped on medical professionals this year, Borrero said she doesn’t consider herself a hero for the work she and her colleagues do — irrespective of the circumstances. “Being a nurse is in me. It’s part of who I am — it’s what I love to do. There’s nothing else I would rather do than to help people when they need me.”