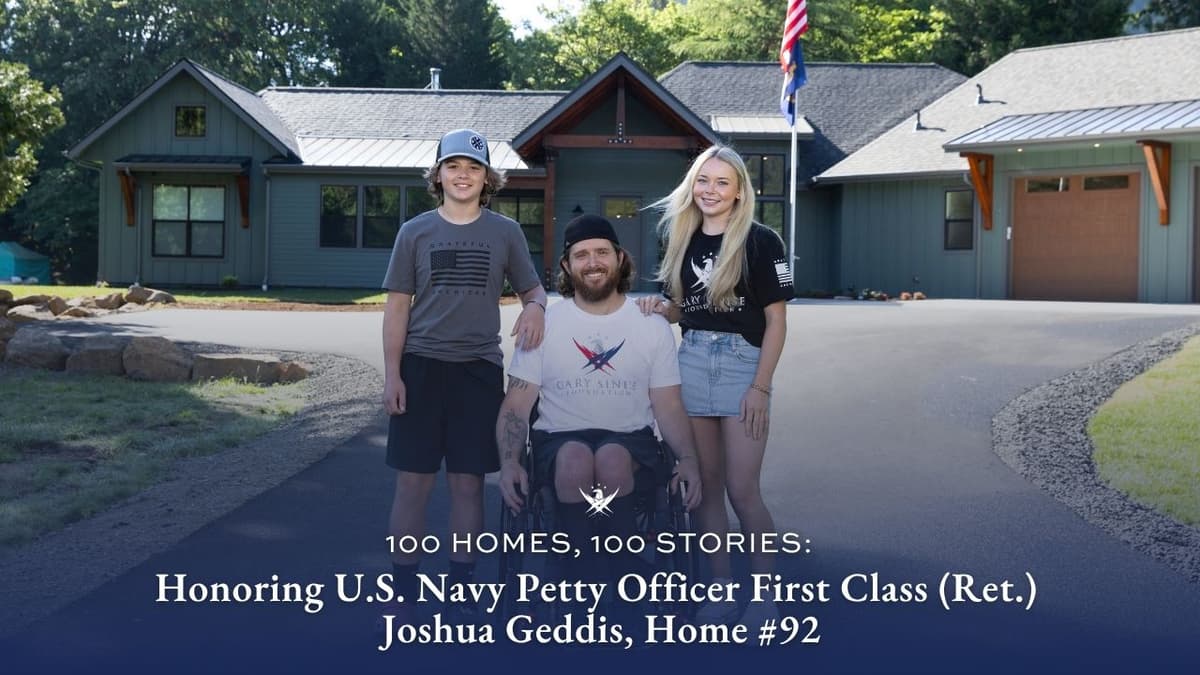

Combat injury spurs new mission for Army veteran and fundraiser for the Gary Sinise Foundation

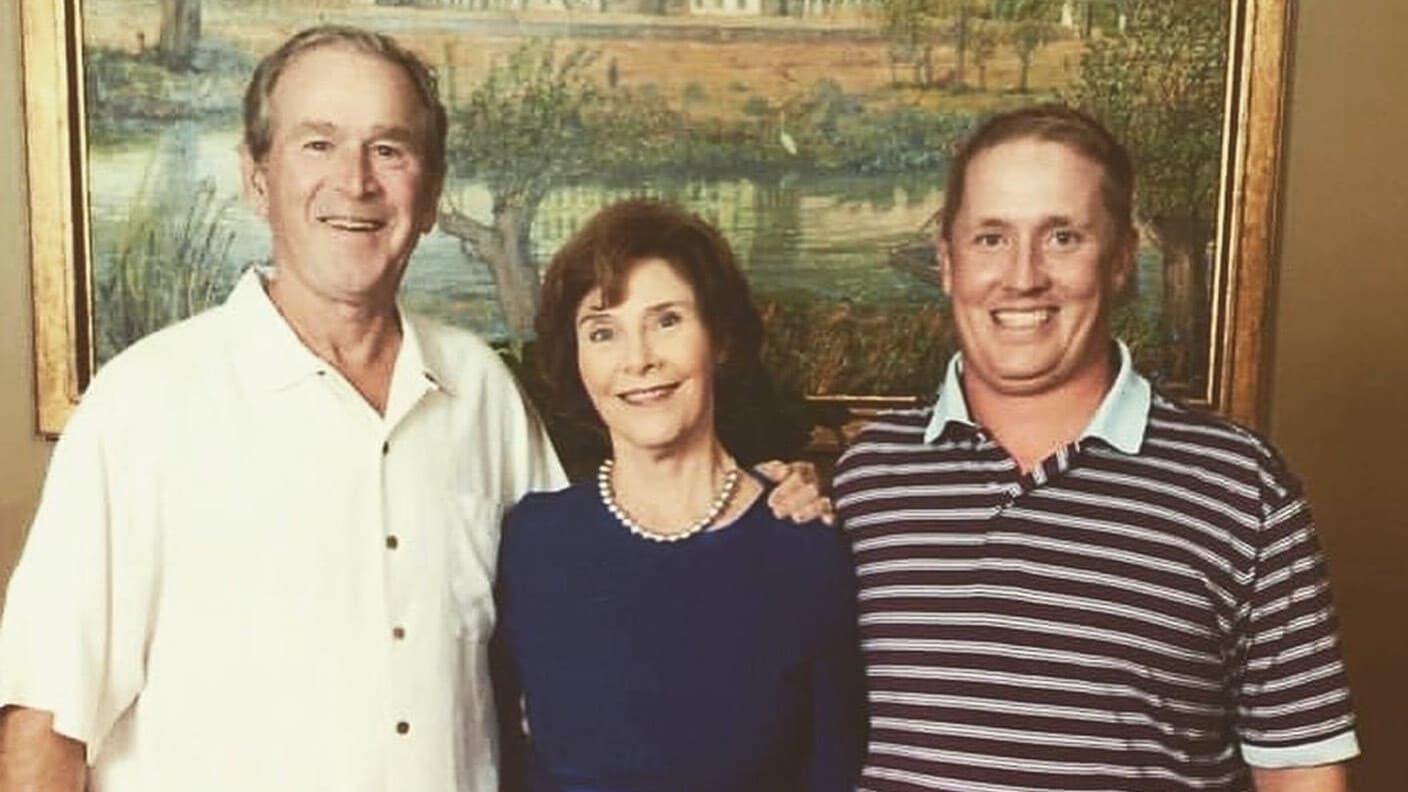

It was nearly time to leave their Dallas hotel room for the George W. Bush Presidential Center. Timothy Gaestel and his wife, Adria, were among the guests at the debut of Portraits of Courage, a series of oil portraits painted by President Bush featuring veterans, like Gaestel, who served in post 9/11 conflicts.

Before leaving the hotel, Gaestel went into the bathroom and freshened up. Eyeing the scale, he stepped on it out of curiosity. When the needle finally settled on the weight, Gaestel stood in disbelief. The date, May 21, 2017, is seared in his memory.

The former Army sergeant has been on a mission since, helping struggling veterans cope with their mental and physical injuries, using his story as a case in point. And it is why he is fundraising for the Gary Sinise Foundation.

Gaestel joined the Army right out of high school. He planned to utilize all four years in the military as a training ground to get in shape to play college football — preferably as a Longhorn at the University of Texas. On the day he was scheduled to go to Basic Training, he and several other recruits watched the news in disbelief as two passenger airliners slammed into the World Trade Center in New York City.

Gaestel enlisted during a time of relative peace, but in less than a year, he was on the ground near the Afghan-Pakistan border and engaged in the opening salvo of the United States’ war on terrorism.

For a 19-year-old kid overseas and far away from Austin, Texas, he said, “Seeing other cultures and walking through a house and seeing a mother spank her little boy on the butt because they were being out of control in the house, taught me how much we are all exactly the same around this world. We just want our kids to have a better life.”

With one combat deployment under his belt, Gaestel and his unit from the 82nd Airborne Division returned home in March 2003 only to find out that they would be deploying to Iraq in a matter of months. Ten days after arriving in Baghdad, two roadside bombs detonated by his vehicle, blowing fist-size shrapnel into his Humvee, and penetrating his lower back.

The damage to his mind, he explained, has been far worse than the scars etched in his back. The once chiseled athlete, a standout on the football field and track, began putting on weight, a lot of weight. No longer able to exercise like before — for fear of making the back pain worse — he fell into depression, retreating away from family and friends and avoiding social gatherings.

For his nagging pain, the VA issued him prescription painkillers like Vicodin, and antidepressants to improve his mood. Coping with back pain was hard enough, but trauma he experienced in Iraq became a different problem.

Within the first six months of leaving the military, he said the police issued him a speeding ticket on three separate occasions. But his driving fast on the freeway was not intentional. In Iraq, Gaestel became conditioned to expect a hidden IED planted in the road or intermixed with trash lying off to the side. He expected the real possibility of a bomb thrown towards his car while it passed underneath an overpass. Speed became a lifesaver. Driving fast on the freeway, then, was not intentional. It was instinctual.

Alcohol, too, became problematic when he took a part-time job at a bar. “Lucky for me, I didn’t have a drinking problem, but I had a ‘drinking while I’m on Vicodin problem.’” He was dropping classes at Austin Community College while underperforming in the courses he stuck with.

“I was so numb to everything that was happening. I didn’t realize how bad it had gotten.”

It was then that his father, Richard, who sensed his son falling deeper into a hole of despair and poor decision making, took him out for a round of golf at Lions Municipal Golf Course near their home in Austin.

Strolling the greens together, each hole became a lesson Richard shared with him about the game or the famed course. He told his son of the Texas greats who left their mark on Lions like Hall of Famers Ben Hogan and Sandra Haynie.

They played 18 holes that day. Never once did Gaestel think about his back pain. Never once did he think about going out for drinks that night. And never once did he think about what he saw in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Gaestel does not equivocate when explaining how the sport saved his life. “I have friends that have killed themselves post serving, and I think how fortunate I am that I found this game. Instead of dwelling on my injury and thinking about all the problems that I have, I just kept wanting to get better at this stupid golf game.” He is now the head golf coach at Vista Ridge High School and teaches freshmen.

In the last three years, Gaestel has shed over 80 pounds, going from wearing a size 44 to 32. He overhauled his diet like he did his exercise regimen. No more soda. No more carbohydrates. No more processed foods. And no more sugar.

Then came running.

The more weight he has dropped this year, the more mileage he adds to his runs, and the further away he gets from the anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder leftover from two combat deployments. Golf may have saved Gaestel but running breathed new life into him.

“I feel like a kid again,” he said. “I honestly get up every day at six and run four miles, and I didn’t think I would do that ever again.” He still has mild pain in his back though no longer needs prescription medications to deal with it — opting instead for healthier, more holistic alternatives.

The night his portrait was unveiled at the George W. Bush Center was the night he took stock of what had become of his physical and mental injuries. He was not just overweight; he was obese, with 254 pounds to show for it. The lessons that have come with the weight loss and mental anguish in those earlier years when he needed help, he is applying in earnest to veterans needing support.

“Without a veteran having a mission or purpose or something to feel excited about,” Gaestel said, such as golf or running or fishing, “That’s the killer right there. That’s what is causing people damage the most.”

“I know there are people struggling, and they’re struggling because they just haven’t figured it out. And I feel like I can give them the secret.”

Since September, Gaestel has been pounding the pavement, running mile after mile for an organization that has lent a hand to veterans and service members alike (logging over 70 miles since September 29). “The Gary Sinise Foundation has never done anything for me,” he explained about not being on the receiving end of any monetary assistance.

“I’m going to run and raise money and hope my friends and family and everyone that follows me on social media would care about helping an organization that I know has helped my friends.”

As for his portrait, the next time he sees President Bush — now nearly 100 pounds slimmer — Gaestel said, “He might not even recognize me, and he painted my portrait!”