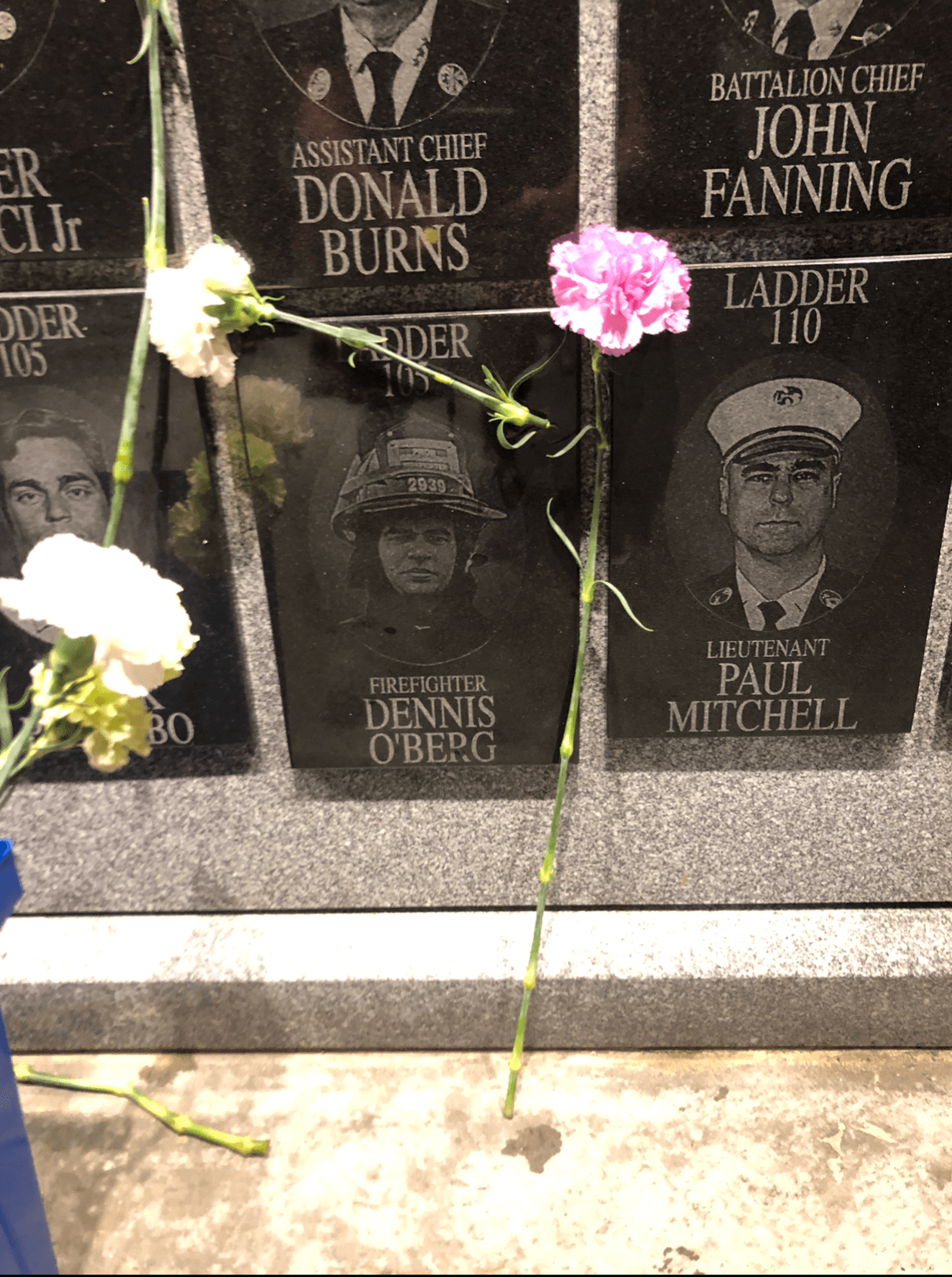

The Brooklyn Wall of Remembrance Honors the Lives of First Responders Lost on 9/11

The faces of the men and women engraved on the Brooklyn Wall of Remembrance tell a story not about their untimely deaths but of the selfless sacrifice made so that others may live. Their names are engraved as a permanent reminder of the heroism that took place during an unprecedented time in American history.

On a day when the nation came under attack on the morning of September 11, 2001, they are the ones whose courageous actions are never forgotten.

Sirens wailed, and people screamed after American Airlines Flight 11, en route to Los Angeles from Boston, slammed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. The fireball explosion sent ashen-grey smoke and fire billowing into the air as debris rained down on lower Manhattan. The alarm requesting first responders began to ring.

Disbelief and confusion as to how an airplane could crash into one of the 110-story-high towers quickly turned to utter panic and terror. Twenty minutes after the first tower had been hit, United Airlines Flight 175, also bound for Los Angeles from Boston, roared low over the city.

Onlookers gasped as the plane careened into the South Tower of the World Trade Center. In what sounded like a bomb going off, the blast and inferno spilled out the side, triggering pandemonium below.

The ringing became a fever pitch as 9-1-1 calls surged. New York City firefighters and paramedics, law enforcement from the NYPD and Port Authority, and other first responder units from across the metropolis responded in earnest to the unfolding devastation leveled on one of the most iconic skylines in America.

When others were fleeing from the burning towers, they were rushing in, climbing up the stairways, floor by floor, to rescue and evacuate as many people as possible.

"Compassion, generosity, and commitment,” explained Monsignor John Delendick, an FDNY chaplain since 1996, were the values that guided firefighters and other first responders that day.

Monsignor Delendick arrived on scene at the World Trade Center shortly after finishing mass at St. Michael’s Catholic Church in Brooklyn. As he was driving into lower Manhattan, caught in the gridlock that had ensnared Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, he caught sight of a large plane flying in an area generally reserved for smaller aircraft.

"Why is that plane so low and flying so fast?” he remembers thinking about the commercial airliner flying over the Hudson River. Moments later, United Airlines Flight 175, the very aircraft he saw fly past him, crashed into the side of the South Tower.

When Delendick arrived at the Incident Command Post, he said the look on the faces of senior leaders in charge was telling of the gravity of the situation awaiting first responders, "I’ve never seen the concern or fear ever on some of these chiefs that I saw that day because they realized this was not going to be a good turnout.”

With smoke and debris billowing from the towers, Delendick and first responders on the ground watched in horror as people trapped in the floors above the impact areas took fate into their own hands; leaping from the blown-out windows and falling to their deaths.

At 9:59 a.m. Eastern Standard Time, the South Tower collapsed. Less than an hour later, at 10:28, the North Tower collapsed. "You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face,” he said about the hellish scene that engulfed the city, leaving it unrecognizable.

When Delendick speaks to grieving families who lost a loved one on 9/11, he shares with them a profound lesson drawn from his faith about the heroic actions carried out by first responders.

"When they ran into the buildings and ran up those stairs, they were no longer climbing the stairs of the World Trade Center; rather, they were climbing the hill of Calvary with Jesus.”

In the days and weeks that followed the attacks, first responders, volunteers, and search and rescue units from all over the country, including several from overseas, descended on ground zero, trying in vain to recover the bodies of hundreds of unaccounted people.

Buried underneath the weight of concrete and steel, not all were found. Many who perished in the collapse of the towers are forever entombed in the former sight of the World Trade Center.

Among the 2,753 lives who perished that September day were 343 firefighters and paramedics who served in the city’s five boroughs, 23 officers from the NYPD, 37 Port Authority officers including an explosives detection canine named Sirius, and beloved FDNY chaplain, Father Mychal Judge.

The memory of the fallen, 417 in all, are honored on the Brooklyn Wall of Remembrance at MCU Park (formerly KeySpan Park) on Coney Island, where photos (measuring 12 inches by 12 inches) of each first responder are laser-engraved alongside their name, rank, and teams organized on three granite panels.

The wall features several bronze reliefs. One depicts two grieving firefighters, Captain Luke Lynch from Engine 201 and Lt. Dennis Farrell from Squad 1; the second shows NYPD detective Joseph Vigiano standing next to Port Authority police officer David Lim kneeling next to his K-9, Sirius; and the third shows the skyline of New York City before the twin towers fell.

In October 2001, Brooklyn native Sol Moglen hatched an idea to create a memorial for his hometown first responders. Of the 137 Brooklyn firefighters, paramedics, and police officers who never made it home, only 15 of their bodies were ever recovered from the rubble.

Working alongside FDNY Chaplain, Rabbi Joseph Potasnik, and with seed money from Mark Scharfman, the Brooklyn Wall was unveiled a year later. The laser-engraved images feature 155 first responders hailing from firehouses and precincts in the borough. What appeared to be finished, and an idea that had come full circle, turned out to be only the beginning for Moglen.

New York City’s fire and police departments are steeped in family tradition. Generations have, at one time or another, sworn an oath to serve and protect their fellow citizens. Fathers serving at the same time as their sons, and brothers serving alongside brothers is not out of the norm at either department.

For Moglen, it became apparent that the wall needed to be expanded to include every first responder who died on 9/11. Raising enough money to pay for the next iteration of the wall, however, was another question for him and his team of volunteers at Ebbets Field Wall of Remembrance Foundation. The nonprofit dedicated to raising money to build a memorial to honor first responders killed on 9/11.

In June 2003, during a USO trip to Iraq, Gary Sinise fortuitously met John Vigiano, a retired FDNY captain who had lost both his sons on 9/11. Their friendship flourished in the months and years that followed. In November 2003, Vigiano introduced Sinise to the men at Ladder 132 in Brooklyn, the same firehouse where John Jr. had once served.

Among the firefighters on duty that evening was Lieutenant Mike Hyland, who first told Sinise about the Brooklyn Wall and aspirations many held for its expansion. The two kept in touch and on July 14, 2006, Hyland, along with retired Fire Marshall Rod Lennon and Lieutenant Bill Schillinger, brought Sinise, who was in town to film scenes for "CSI: NY,” to Coney Island to meet Moglen and visit the wall.

The visit became a turning point, Moglen explained. Sinise was so moved by the memorial and the plans for its expansion, that two weeks later he wrote a personal check for $25,000 to go toward its funding. But he didn’t stop there. Sinise also proposed donating the Lt. Dan Band to host a fundraising concert for the wall.

On August 11, 2007, in front of a sold-out audience at Brooklyn College’s Walt Whitman Theater (renamed Claire Tow Theater in 2019), Gary Sinise and the Lt. Dan Band held court during a concert that raised thousands of dollars for expansion of the Brooklyn Wall.

"So many people — friends of mine who lost their sons, friends who lost their brothers and fathers — were sad, but at the concert, I saw these people so happy,” said John Plant, a retired battalion chief and former captain at Ladder 132 who was involved in the fundraising efforts.

On May 18, 2008, what had been years in the making finally came to fruition when additional portions of the Brooklyn Wall of Remembrance were dedicated. "I felt I did something special for the families,” explained Moglen. "It gave them someplace to come. It gave them closure.”

The wall does not speak of death, said Monsignor Delendick, who gave the invocation during the ceremony, "It talks about life, it talks about the good times you had with the people on the wall, it talks about their family life.”

"It’s just so poignant and beautiful,” said Hyland. "You look at all your buddies on the wall, and it’s good because it memorialized them, it’s done beautifully, and the guys are all together.”

Today, the Brooklyn Wall of Remembrance stands as a boundless story and an enduring tribute to 417 of New York City’s brave men and women (and canine) who gave their lives nearly nineteen years ago.

"When you have faces, it really connects who these people are and that they had a life,” said Moglen, "We should never forget them.”